I am not sure why I love reading about the lives of songwriters.

And learning many of their songs.

And then sharing what I have learned in one-hour musical programs at retirement communities, public libraries, senior centers, memory cafes, and coffeehouses.

But I do!

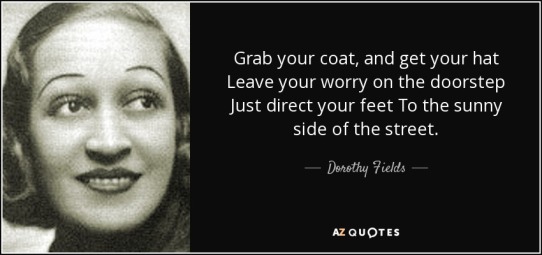

The most recent program I put together with jazz pianist Joe Reid features the life and music of Dorothy Fields.

She was a terrific lyricist who co-wrote hit songs from the late 1920s right through the early 1970s.

When many of her friends and contemporaries — such as Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, the Gershwin brothers, Oscar Hammerstein, Larry Hart — were either dead, discouraged or stymied by evolving musical trends such as folk and rock, Dorothy Fields achieved one of her biggest hits on Broadway, the wonderful musical Sweet Charity.

She was 61 years old.

Go, Dorothy!

Dorothy Fields was born into a theatrical family and raised to be a wife and mother — NOT an actress or a songwriter (both of which occupations her parents strongly discouraged…)

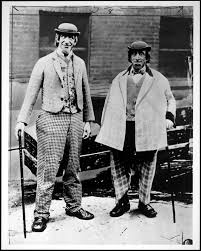

Her father was half of a very famous and successful vaudeville team called “Weber & Fields” who had started as childhood friends performing in the Bowery and had risen as adults to the top ranks of theatrical entertainment in the US .

Eventually her father tired of performing and touring, and began to produce shows by other people, including a young team of songwriters named Rodgers & Hart, who were friends with Dorothy’s older brother Herbert (having collaborated together on original theatrical productions while attending Columbia University).

Dorothy and her three siblings had been exposed to theater their entire lives, and Dorothy played lead (male!) roles in amateur theatrical productions at her high school, The Benjamin School for Girls at 144 Riverside Drive on the upper west side of Manhattan.

So it seems a bit surprising (to me, anyways) that her parents attempted to dissuade her from a life in the theater.

When she was growing up, the family had blank books into which everyone was encouraged to jot down ideas for jokes, skits, plots and routines — which served as inspiration when a new show was being created by her father.

And both of her brothers were very successful on Broadway and in Hollywood as writers.

In fact, later on in her life, Dorothy and her older brother Herbert co-wrote the librettos (aka scripts) for shows by Cole Porter and Irving Berlin — including the smash hit, Annie Get Your Gun — which had originally been HER idea as a starring vehicle for her friend Ethel Merman.

Dorothy was supposed to write the songs with one of her most beloved collaborators, Jerome Kern, until Kern unexpectedly died.

Among other hits, she and Jerry had co-written “The Way You Look Tonight,” which won an Academy award for best song in a motion picture in 1936.

After a period of mourning, she and her producers — Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein — asked Irving Berlin if he would consider joining the project.

And the rest is history…

But Dorothy was born in 1905, when middle and upperclass women were expected to become wives and mothers (not actresses or songwriters or librettists).

Women didn’t get the right to vote until 1920 — when Dorothy was 15 — and her life illuminates many of the social changes that unfolded in the US until her death in 1974.

Dorothy managed to finesse her parental/societal expectations by BOTH marrying young (to a doctor) AND pursuing a career as a lyricist.

Although she worked with a “who’s who” list of composers during her long career, three of them stand out as being particularly significant in her creative life: Jimmy McHugh, Jerome Kern, and Cy Coleman.

Jimmy McHugh was a Catholic pianist from Boston, where he had left a wife and son (whom he dutifully supported from afar) when he moved in his 20s to Manhattan to find work as both a composer and business manager for music publishing companies.

He crossed paths with Dorothy when her friend J. Fred Coots — whom she had met while golfing and who went on to write hits of his own such as “You Go To My Head” and “Santa Claus Is Coming To Town” — began introducing her to music publishing companies as a budding lyricist.

Dorothy and Jimmy hit it off creatively — and possibly romantically — although they were both extremely protective of their private lives and mindful about the potential for bad publicity.

During their ten-year collaboration they wrote hits including, “I Feel A Song Coming On,” “On The Sunny Side Of the Street,” and “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.”

I love learning that “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” was not an immediate hit (one critic called it “sickly” and “puerile”) and was cut from two different shows before it finally caught on as part of the Blackbirds of 1928.

Persistence, persistence, persistence!

Her next significant collaborator was Jerome Kern. They wrote songs — including “Pick Yourself Up,” “I Won’t Dance,” and “A Fine Romance” — for Hollywood movies with stars such as Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire.

Here she is with Jerry Kern (on her left) and George Gershwin (on her right) at a nightclub in the 1930s.

Jerome Kern was older than many of his contemporary songwriters (Gershwin, Arlen, Youmans and others looked up to him when they were starting to write songs) and had a reputation for speaking his mind — and not suffering fools gladly. Some people in the entertainment industry were intimidated by him.

But not Dorothy. She loved him and even gave him a nickname which few others would have dared to choose: “Junior” (Dorothy was 5″ 5″ tall and towered over Kern, who was much shorter).

I have wondered whether the lyrics she wrote for their song “You Couldn’t Be Cuter” might have been something of an “in joke” between the two of them.

Here’s a version of that song — combined with an earlier hit she wrote with Jimmy McHugh, “Exactly Like You” — that I recorded with pianist Doug Hammer earlier this year.

Her third significant collaborator was Cy Coleman, a composer who had already written hit songs with Carolyn Leigh (including “The Best Is Yet To Come,” “Hey, Look Me Over,” and “Witchcraft”) before he met Dorothy at a party.

She was 59 years old, and he was 35.

He asked her if she might be willing to explore working together, and she allegedly said something like, “Thank g-d someone asked me…yes!”

They ended up collaborating on a musical inspired by a Fellini film — “Le Notti Di Cabiria,” about a prostitute looking for love — which Bob Fosse and his wife Gwen Verdon had seen and which had immediately inspired Fosse to start working on a musical version for Verdon to star in.

With Neil Simon added to the creative team as librettist, Fosse, Verdon, Fields and Coleman created what became the hit musical Sweet Charity — which went on to become a movie starring Shirley MacLaine and John McMartin, and which gave us songs such as “Hey, Big Spender,” “I’m A Brass Band,” and “If My Friends Could See Me Now.”

Dorothy Fields achieved a remarkable level of success in a male-dominated industry —where women were expected to be on stage, not behind the scenes as part of the creative team.

She was not a glamour girl nor a prima donna — although she was always very well-dressed and had separate closets for her shoes, dresses, suits, sportswear, and evening gowns.

She was reliable, respectful and professional.

And she was a hard-worker.

At one point she said, “I wrote the words to ‘I Feel a Song Coming On,’ but I don’t believe a word of it. A song just doesn’t ‘come on.’ I’ve always had to tease it out, squeeze it out. Ask anyone who writes — it’s tough labor and I love it.”

I’ll end with two more gems she wrote with Jimmy McHugh — “Don’t Blame Me” and “I’m In The Mood For Love” — which I recorded with pianist Doug Hammer at his terrific studio, Dreamworld, in Lynn, MA.

Thank you to Dorothy Fields and her many collaborators for writing such terrific songs.

Thank you to pianist Steve Sweeting for recording “I Feel a Song Coming On” and “The Way You Look Tonight” with me many years ago at his apartment in Brighton, MA.

And thank YOU for reading and listening to this blog post.